9.3. Partial Composition: Restructuring Operads

After one stares at the definition of an operad for quite some time, they will realize that the vast and mysterious diagrams and indices are really just for booking keeping, and that the idea is actually rather quite intuitive. And of this bookkeeping is what makes operads a bit annoying; we are constantly having to think about an arbitrarily long tensor products. However, Freese has pointed out in his text that we can actually rephrase the language of operads more simply by replacing the arbitrarily long composition morphism with a partial composition morphism. However, this itself is not trivial.

Let \(X\) be a set, and consider the endomorphism operad \(\aend_X(n)\). For any \(f \in \hom_{**Set**}(X^n, X)\), we can choose \(g_i \in \hom_{**Set**}(X^{a_i}, X)\) for \(a_i \in \mathbb{N}\) with \(i = 1, 2, \dots, n\). Composition can then be defined pointwise:

However, what if we decided to build this function another way; perhaps, handling one \(g_i\) at a time? The way we could do this is by inserting a \(g_i\) one at a time:

Given that we'd have a total of \((n + a_i -1)\)-many inputs, this then defines a composition operator

for each \(n, a_i \ge 0\). We can then repeatedly apply this composition operator to build the same function that our operadic composition does.

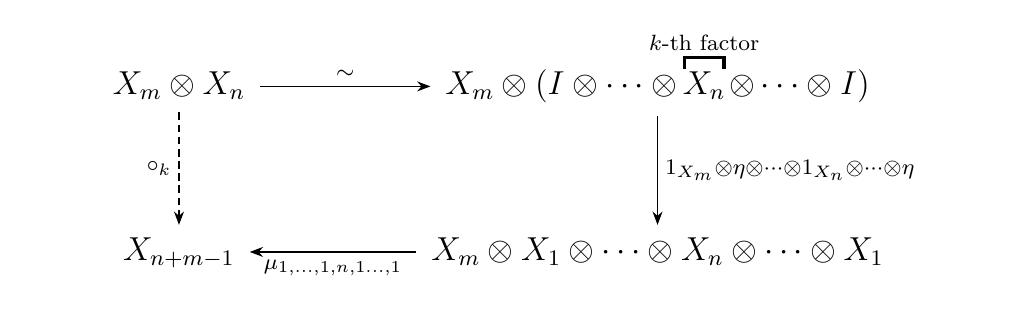

Let \(X\) be an operad in a symmetric monoidal category \(\cc\). Then for each \(n, m \ge 0\), we define the partial composition operator \(\circ_k: X_n \otimes X_m \to X_{n + m - 1}\) as the composition of the arrows pictured below.

In other words, the partial composition operator \(\circ_k\) on \(X_m \otimes X_n\) is the same as our original

composition operator \(\mu\) applied to \(X_m \otimes X_1 \otimes \cdots \otimes X_n \otimes \cdots \otimes X_1\).

In other words, the partial composition operator \(\circ_k\) on \(X_m \otimes X_n\) is the same as our original

composition operator \(\mu\) applied to \(X_m \otimes X_1 \otimes \cdots \otimes X_n \otimes \cdots \otimes X_1\).

It was Fresse who demonstrated in his gigantic text that the partial composition operator can equivalently construct operads. The strategy he used is as follows: we first investigate what properties (i.e. diagrams) that the partial composition operator satisfies. Then, we forget that we ever had on operad, but we rather consider a sequence of objects which are basically operads, but whose composition operator has now been replaced by the partial composition operator. Fresse showed that these objects then form a category, and that this category is isomorphic to the category of operads, thereby demonstrating an equivalence of operad definitions and paving the way for simpler calculations in demonstrating that something is an operad.

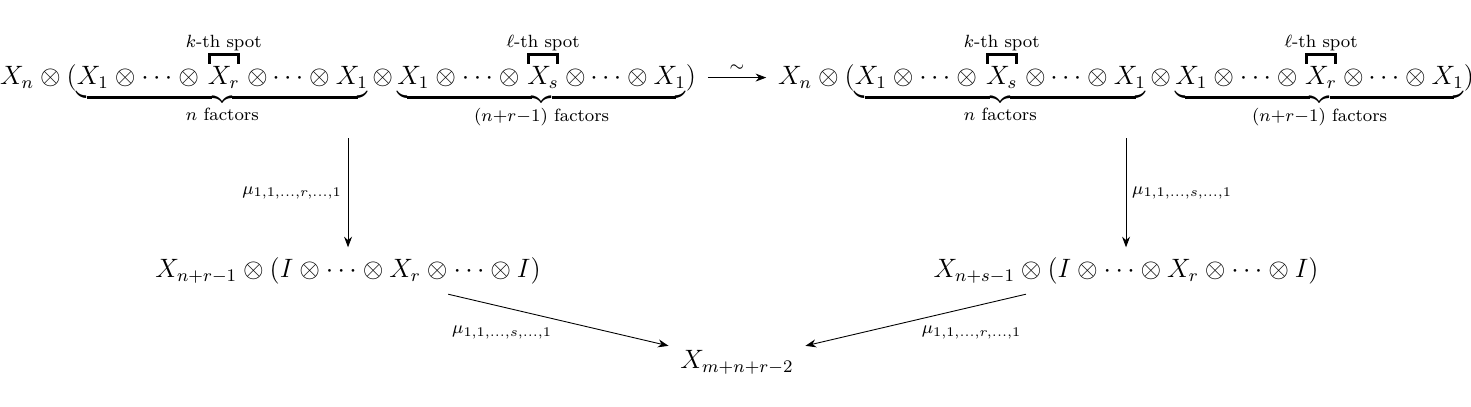

Thus we demonstrate properties of the partial composition operator. Let \(X\) be an operad and recall the associativity pentagon given in OP1. In the associativity diagram, replace \(X_{a_i} = X_1\) except \(X_{a_p} = X_r\) for some \(p \le n\), and set \(X_{k_{i,j}} = X_1\) except for \(X_{k_{p,q}} = X_s\) for some \(q \le a_p\). Then we get the commutative diagram below.

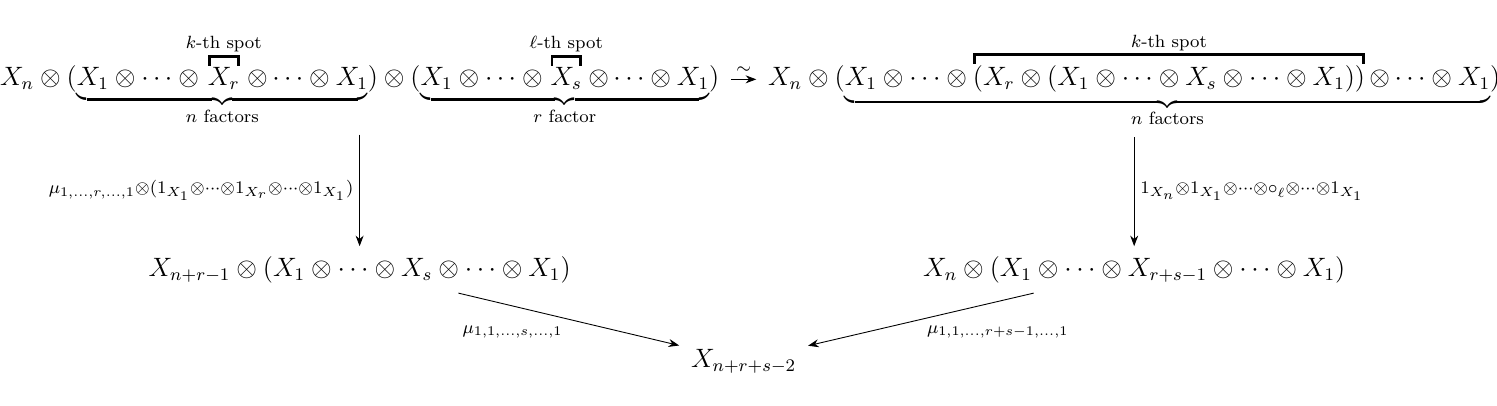

With similar substitutions, we also get that the diagram below commutes.

With similar substitutions, we also get that the diagram below commutes.