3.4. Cartesian Products and Direct Sums.

In group and ring theories, we can make sense of the idea of a cartesian product of groups or rings. Thus it is again no surprise that we can construct cartesian products of modules.

However, we shall see a theme that is common in most areas of mathematics: infinite products behave differently than finite products. In fact, it usually turns out that our intuitive definiton for the products of our objects (in our case, modules) is usually wrong and cumbersome, even though it feels intuitive. That is, we generally want to define products using the cartesian notion, but this usually just gives us more problems.

The alternative is to come up with a definition of multiplication that is cartesian for finite products, but is not exactly cartesian for infinite products. This will make sense once we are more specific by what we mean.

Let \(M_1, M_2, \dots, M_n\) be a set of \(R\)-modules. We define

as the cartesian product of these \(R\)-modules whose elements are of the form \((x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n)\) where \(x_i \in M_i\) for \(i \in \{1, 2, \dots, n\}\).

More generally, if \(\{M_\alpha\}_{\alpha \in \lambda}\) is an arbitrary family of \(R\)-modules then \(\displaystyle \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda} M_\alpha\) is the arbitrary cartesian product.

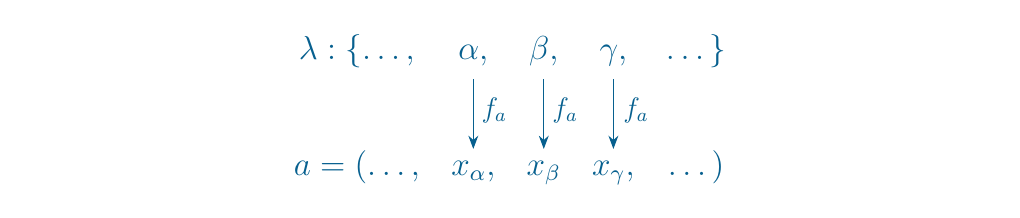

\textcolor{purple}{You may now ask how we notate, or even describe these elements. We can't put them in a tuple, since they're not finite. We could put them in a tuple like "\((x_1, x_2, \dots)\)", where the ellipsis implies an infinite list of elements, but that would only take care of at most countable families of \(R\)-modules. } \textcolor{MidnightBlue}{ \ \ \indent Instead, we use the following idea as elements of \(\displaystyle \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda} M_\alpha\) being "functions." This is an abstract, yet quite useful strategy used in different areas of mathematics to deal with arbitrary products. \ \ \indent Let us first literally describe our elements. An element \(\displaystyle a \in \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda} M_\alpha\) is uniquely determined by selecting one element \(m_\alpha \in M_\alpha\) for each \(\alpha \in \lambda\). This is how a tuple works. For example, in \(\mathbb{R}^3\), we separately pick 3 elements out of 3 separate copies of \(\RR\) to form a tuple \((x_1, x_2, x_3) \in \mathbb{R}^3\). \ \ Thus for each \(\displaystyle a \in \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda}\) we may associate \(a\) with a function \(f_a: \lambda \to \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda}M_\alpha\) which iterates through all \(\alpha \in \lambda\) and picks out an element \(M_\alpha\). For example, if we know that, for \(i \in \lambda\), the \(i\)-th coordinate of \(a\) is \(x\), then \(f_a(i) = x\). }

\textcolor{NavyBlue}{

The above diagram illustrates our descriptions so far, where

in the case above we have that the \(\alpha\)-th element of \(a\)

is \(x_\alpha\), the \(\beta\)-th element of \(a\) is \(x_\beta\), and

so on. With

that said, we can now restate that

\textcolor{NavyBlue}{

The above diagram illustrates our descriptions so far, where

in the case above we have that the \(\alpha\)-th element of \(a\)

is \(x_\alpha\), the \(\beta\)-th element of \(a\) is \(x_\beta\), and

so on. With

that said, we can now restate that

and move onto understanding why we want to adjust our definition for multiplication of \(R\)-modules. }

It turns out that we can make the arbitrary cartesian product into an \(R\)-module.

If \(\{M_\alpha\}_{\alpha \in \lambda}\) is a family of \(R\)-modules, then \(\displaystyle \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda}M_{\alpha}\) is an \(R\)-module.

- Abelian Group. First observe that \(\displaystyle \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda} M_\alpha\) is an abelian group if we realize the identity is the zero map \(f\) (i.e., the "tuple" of all zeros) and endow an operation of addition as follows. For \(f_1, f_2 \in \displaystyle \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda} M_\alpha\) we have that

for all \(\alpha \in \lambda\). Note that this makes sense since \(f_1(\alpha), f_2(\alpha) \in M_\alpha\). Hence the sum will be an element in \(M_\alpha\). Also, if \(f \in \displaystyle \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda} M_\alpha\), we define the inverse to be \(f^{-1}\) where \(f^{-1}(\alpha) = -f(\alpha)\). Commutativity is inherited from commutativity of all \(M_\alpha\), and so we have an abelian group. * Ring Multiplication. Let \(a \in R\). Then define

for all \(\alpha \in \lambda\). Observe that, since each \(M_\alpha\) is an \(R\)-module, we have that \(f(\alpha) \in M_\alpha \implies af(\alpha) \in M_\alpha\) for all \(\alpha \in \lambda\). Thus our multiplcation is well-defined. It is then a simple exercise to check that the axioms of an \(R\)-module are satisfied via our operations.

Since our above argument was a bit abstract, we reintroduce it in the language of finite products. Again, we can turn a finite cartesian product of \(R\)-modules into an \(R\)-module with the following operations.

- 1. Let \((m_1, m_2, \dots, m_n), (p_1, p_2 ,\dots, p_n) \in M_1 \times M_2 \times \cdots \times M_n\). Then let us define addition of elements as

$$ (m_1, m_2, \dots, m_n) + (p_1, p_2 ,\dots, p_n) = (m_1 + p_1, m_2 + p_2, \dots, m_n + p_n). $$ * 2. For any \(a \in R\) and \((m_1, m_2, \dots, m_n) \in M_1 \times M_2 \times \cdots \times M_n\) we define scalar multiplication as

Again, it is then simple to check that this satisfies the axioms for an \(R\)-module.

\textcolor{NavyBlue}{When we think of multiplying sets together, cartesian products usually come to mind. They are the most natural to us since it has been ingrained in us to think this way since primary school. However, it turns out in many areas of mathematics that the cartesian approach to defining multiplication of objects leads to undersirable properties, and objects often misbehave under a cartesian definition. \ \ As we said earlier, the problems arise when the products get infinite. Hence the solution involves defining a new kind of multiplication which is the same as a cartesian product for finite products, but is different for infinite products.}

This leads to the concept of direct sums, which we will use instead of cartesian products (we will soon see why).

Let \(\{M_\alpha\}_{\alpha \in \lambda}\) be a family of \(R\)-modules. Then we define the direct sum of \(\{M_\alpha\}_{\alpha \in \lambda}\) as

The only difference between the direct sum and the cartesian product is that, for any point \(\displaystyle a \in \bigoplus_{\alpha \in \lambda} M_\alpha\), all indices of \(a\) are zero except for finitely many indices. So only finitely many indices are nonzero for a direct sum, while in a cartesian product there may be finite, countable or uncountably many nonzero indices.

\textcolor{purple}{Thus, note that for a finite product, the direct sum and the cartesian product are the exact same thing}. There is no difference when the product is finite. In other words,

The direct sum of a family \(\{M_\alpha\}_{\alpha \in \lambda}\) of \(R\)-modules is an \(R\)-module. In fact, \(\displaystyle \bigoplus_{\alpha \in \lambda} M_\alpha\) is an \(R\)-submodule of \(\displaystyle \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda} M_{\alpha}\).

Note that \(\displaystyle \bigoplus_{\alpha \in \lambda} M_\alpha \subset \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda}M_\alpha\). Thus we can use the submodule test to check if is in fact an \(R\)-module. Observe that for any \(a, b \in R\) and \(\displaystyle f_1, f_2 \in \bigoplus_{\alpha \in \lambda}M_{\alpha}\), we have that

since the function \(a(f_1)(\alpha) + b(f_2)(\alpha)\) will be nonzero for only finitely many values. (In fact, if \(f_1\) is nonzero for \(k\)-many values and \(f_2\) is nozero for \(l\) many values, then \(a(f_1)(\alpha) + b(f_2)(\alpha)\) is nonzero for at most \(k + l\)-many values). Hence this passes the submodule test.

\noindentWhy do we prefer direct sums over cartesian products? \

The answer lies in the following observation. Suppose \(\{M_{\alpha}\}_{\alpha \in \lambda}\) is a family of \(R\)-modules and that for each \(\alpha \in \lambda\) there exists a homomorphism \(\phi_\alpha : M_\alpha \to N\). Let \(a \in \displaystyle \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda}M_\alpha\) and represent \(a\) with the map \(f_a:\lambda \to \displaystyle \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda}M_{\alpha}\). Thus \(f_a(\alpha) \in M_\alpha\) is the \(\alpha\)-th coordinate of our point \(a\).

If we try to define a homomorphism \(\displaystyle \phi : \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda}M_\alpha \to N\) in a natural, linear way such as

where \(\displaystyle a \in \prod_{\alpha \in \lambda}M_{\alpha}\), then observe that the above sum is nonsense. What the hell is an infinite sum of module elements of \(N\) supposed to represent? Also, there's no way to make sure this is even well-defined!

However, if we instead consider \(\displaystyle \bigoplus_{\alpha \in \lambda}M_{\alpha}\), then creating a natural homomorphism \(\displaystyle \phi: \bigoplus_{\alpha \in \lambda}M_{\alpha} \to N\) where again

works out fine. We see that \(\phi\) is valid because \(f_a(\alpha) = 0\) for all but finitely many \(\alpha \in \lambda\). Hence, the above sum will only ever consist of a sum of finite elements.

The next important two theorems demonstrate the importance of the direct sum.

Let \(M\) be an \(R\)-module and suppose \(M_1, M_2, \dots, M_n\) are submodules such that

- 1. \(M = M_1 + M_2 + \cdots + M_n\)

- 2. \(M_j \cap (M_1 + M_2 + \cdots + M_{j-1} + M_{j + 1} + \cdots + M_n) = \{0\}\) for all \(j \in \{1, 2, \dots, n\}\).

Then

\vspace{-0.8cm}

Construct the map \(f:M_1 \oplus M_2 \oplus \cdots \oplus M_n \to M\) as

It is simple to check that this is an \(R\)-module homomorphism. Observe that by (1) \(\im(f) = M\). Now suppose \((x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n) \in \ker(f)\). Then we see that

for all \(i \in \{1, 2, \dots, n\}\). But by (2), we know that no such \(x_i\) can exist. Therefore \(x_1 = x_2 = \cdots = x_n = 0\). Hence, \(f\) is an isomorphism, which yields the desired result.

The above result can be generalized to arbitrary direct sums. However, if we were dealing with cartesian products, we would not be able to generalize the above theorem to arbitrary direct sums.

Let \(M\) be an \(R\)-module and suppose \(\{M_\alpha\}_{\alpha \in \lambda}\) is a family of \(R\)-modules such that

- 1. \(\displaystyle M = \sum_{\alpha \in \lambda} M_\alpha\)

- 2. \(M_\beta \bigcap \displaystyle \sum_{\alpha \in \lambda\setminus\{\beta\}}M_\alpha = \{0\}\) for all \(\beta \in \lambda\)

then

\vspace{-0.7cm}

The proof is the exact same as before, although the notation is annoying.