1.6. Functors

At this point, we really have no significant reason to care about categories. They have only so far proved to be an organizatonal tool for concepts of mathematics, but that is about it. In this section, we introduce the abstract notion of a functor which is prevalent everywhere in mathematics. Functors are ultimately a helpful notion which we care a lot about, but in order to define a functor we first needed to define categories. But as we have defined categories, we move on to defining functors.

Let \(\cc\) and \(\dd\) be categories. A (covariant) functor \(F: \cc \to \dd\) is a "mapping" such that

- 1. Every \(C \in \ob(\cc)\) is assigned uniquely to some \(F(C) \in \dd\)

- 2. Every morphism \(f: C \to C'\) in \(\cc\) is assigned uniquely to some morphism \(F(f): F(C) \to F(C')\) in \(\dd\) such that \begin{statement}{ProcessBlue!10}

\end{statement}

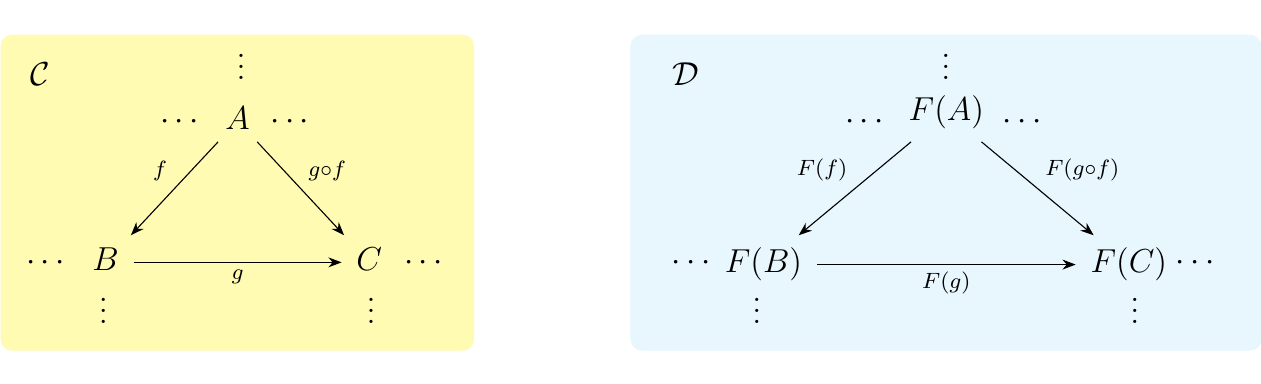

If you have seen a graph homomorphism before, this definition might seem similar. This is no coincidence, and we'll see later on what the relationship between categories and graphs really are. But with that intuition in mind, we can visualize the action of a functor. Below we have arbitrary categories \(\cc\), \(\dd\), and a functor \(F: \cc \to \dd\).

In what follows, we offer some simple and abstract examples that can get us familiar with the behavior of functors. In the next section, we do the opposite, and instead use our abstract understanding of functors to witness functors in real mathematical constructions\footnote{I chose to separate this section and the next to ease the learning curve for functors; both perspectives are necessary for true understanding of a functor.}.

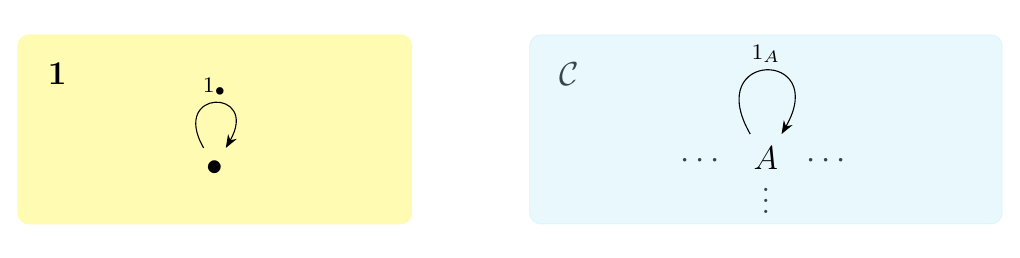

Denote \(\bm{1}\) as the category with one object \(\bullet\) and one identity morphism \(1_\bullet: \bullet \to \bullet\). Then for any category \(\cc\), there exists a unique functor \(F: \cc \to \bm{1}\) which sends every object to \(\bullet\) and every morphism to \(1_\bullet\).

Conversely, there are many functors \(F: \bm{1} \to \bm{\cc}\). Since we only have \(F(\bullet) = A\) for some \(A \in \cc\), and \(F(1_\bullet) = 1_A\), we see that this functor simply picks out one element of \(\cc\). So these functors are in correspondence with the objects of \(\cc\); the picture below may help.

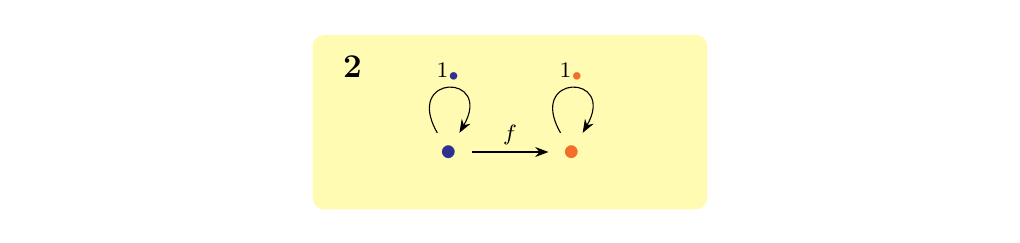

Let \(\bm{2}\) be the category with two objects \(\textcolor{Blue}{\bullet}\) and \(\textcolor{Orange}{\bullet}\) with one nontrivial \(f: \textcolor{Blue}{\bullet} \to \textcolor{Orange}{\bullet}\). The category can be pictured as below.

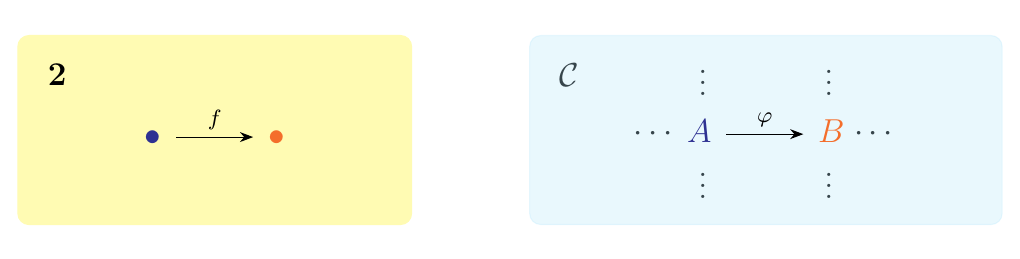

Suppose now that \(\cc\) is an arbitrary category, and that we

have a functor \(F: \bm{2} \to \cc\). Then note that \(F(\textcolor{Blue}{\bullet}) = A\)

and \(F(\textcolor{Orange}{\bullet}) = B\) for some objects \(A, B \in \cc\). Hence we have that

\(F(f) = \phi: A \to B\) for some \(\phi \in \cc\). Below we have the functor pictured.

Suppose now that \(\cc\) is an arbitrary category, and that we

have a functor \(F: \bm{2} \to \cc\). Then note that \(F(\textcolor{Blue}{\bullet}) = A\)

and \(F(\textcolor{Orange}{\bullet}) = B\) for some objects \(A, B \in \cc\). Hence we have that

\(F(f) = \phi: A \to B\) for some \(\phi \in \cc\). Below we have the functor pictured.

Note we suppressed the identity morphisms.

Therefore, we see that this functor simply picks out morphisms \(\phi: A \to B\) in \(\cc\).

So we can say that functors \(F: \bm{2} \to \cc\) are in correspondence with the

morphisms of \(\cc\).

Note we suppressed the identity morphisms.

Therefore, we see that this functor simply picks out morphisms \(\phi: A \to B\) in \(\cc\).

So we can say that functors \(F: \bm{2} \to \cc\) are in correspondence with the

morphisms of \(\cc\).

Consider the very first figure of this section, Figure \ref{figure:functor_def}. In that image we saw three objects \(A,B,C\) get sent to \(F(A),F(B),F(C)\). However, the original commutative diagram involving \(f, g\) and \(g \circ f\) was translated into another commutative diagram in \(\dd\) involving \(F(f), F(g)\) and \(F(g \circ f)\). This is because of the critical property \(F(g \circ f) = F(g) \circ F(f)\) given by a functor. In fact, any commutative diagram translates to a commutative diagram under a functor.

Let \(\cc, \dd\) be categories with \(F: \cc \to \dd\) a functor.

Suppose \(J\) be a commutative diagram in \(\cc\). Then the diagram obtained

from the image of

\(J\) under \(F\), which we denote as \(F(J)\), is commutative in \(\dd\).

It suffices to prove that, for any complete subdiagram \(J'\) of \(J\) involving any two distinct paths

in \(J\), we have that \(F(J')\) is commutative in \(\dd\). But this immediate. Since \(J'\) is commutative in \(\cc\), we have that \(p = q\). Hence we see that

by repeatedly applying the composition property of a functor. Hence \(F(J')\) is commutative of \(J\). Since

Finally, before we move onto the next section and introduce various examples of functors across mathematics, we introduce one of the most important functors in basic category theory.

Let \(\cc\) be a locally small category. Then for every object \(A\), we obtain the covariant hom-functor denoted as

where on objects \(C \mapsto \hom_{\cc}(A, C)\) and on morphisms \((\phi: C \to C') \mapsto \phi^*: \hom_{\cc}(A, C) \to \hom_{\cc}(A, C'))\) where \(\phi^*\) is a function defined pointwise as

Such a functor is naturally of interest in mathematics since it is often of interetst to consider the hom set \(\hom_{\cc}(A, B)\) for some objects \(A, B\) in a category \(\cc\), as it is usually the case that this set contains extra structure. For example, within topology this set is always a topological space, since families of continuous functions can be endowed with the compact open topology. In the setting of abelian groups, this set also forms an abelian group. Much of category theory can actually be done by simply "enriching" hom sets of a category with some extra structure; this is the object of enriched category theory, which we'll introduce later.

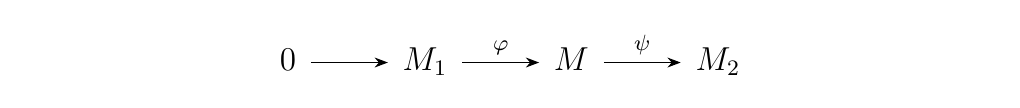

This functor in general also exhibits nice properites. For example, let \(R\) be a ring. Then the sequence below

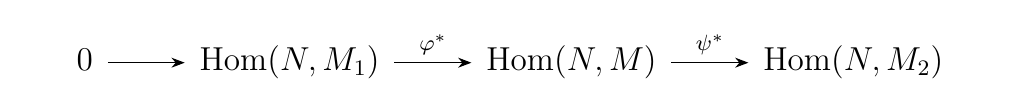

is exact if and only if, for every \(R\)-module \(N\), the sequence

is exact if and only if, for every \(R\)-module \(N\), the sequence

is exact. This result even extends to split short exact sequences. We

also have that for \(R\)-modules \(N\), \(M_1, M_2\) that

is exact. This result even extends to split short exact sequences. We

also have that for \(R\)-modules \(N\), \(M_1, M_2\) that

This result also holds for arbitrary direct sums, so that the hom functor distributes over all direct sums. Even better, we cannot forget that the hom-functor exhibits the tensor-hom adjunction which states that for \(R\)-modules \(N, M_1, M_2\)

More is to be said about this property; we'll later see that this is an example of an adjunction.