2.1. $\mathcal{C

op$ and Contravariance}

Consider a category \(\mathcal{C}\). Then we define the opposite category of \(\cc\), denoted \(\mathcal{C}\op\), to be the category where

- Objects. The same objects of \(\cc\).

- Morphisms. If \(f: A \to B\) is a morphism of \(\cc\), then we let \(f\op : B \to A\) be a morphism of \(\cc\op\).

In this case, composition isn't exactly obvious, so we will explain how that works.

Let \(f: A \to B\) and \(g: B \to C\) be morphisms of \(\cc\). Then we obtain morphisms \(f\op: B \to A\) and \(g\op: C \to B\). In this case \(f\op, g\op\) are composable, and we define composition of \(\cc\op\), denoted as \(\circ\op\), to be the morphism

Moreover, we have the relation \((g \circ f)\op = f\op \circ g\op\).

Taking the opposite category might seem very strange, but we are doing nothing more than just taking the same category and swapping the domain and codomain of every morphism.

Consequently, many properties of morphisms are similarly reversed. For example, if \(f: A \to B\) is monomorphism in \(\cc\), then \(f\op: B \to A\) is an epimorphism in \(\cc\op\). More generally, every logically valid statement that can be made in \(\cc\) using its objects and morphisms can be dualized to achieve an equivalent, logically valid statement in \(\cc\op\) using its objects and morphisms.

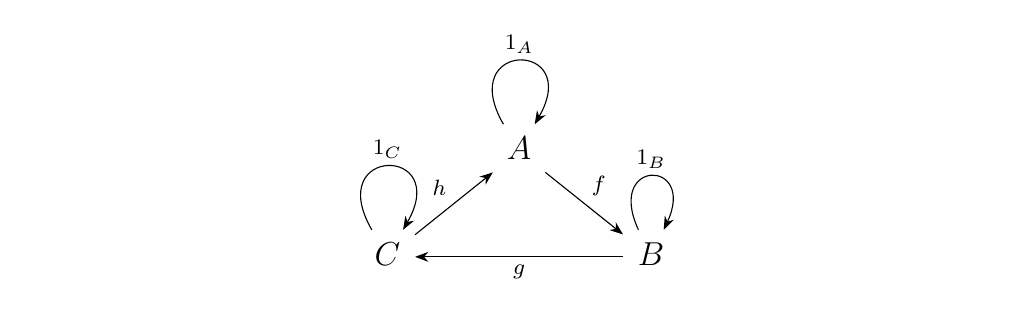

Consider a category \(\cc\) containing \(3\) objects whose morphisms are arranged as follows:

What does the dual category \(\cc\op\) look like? Well, \(\cc\op\)

contains the same objects \(A, B\) and \(C\). As for the morphisms, \(\cc\)

has the three morphisms \(f, g, h\), in addition to their composites.

Therefore, \(\cc\op\) also has three morphisms

\(f\op:B \to A\), \(g\op: C \to

B\) and \(h\op: A \to C\) and their composites. Hence, \(\cc\op\) looks like this:

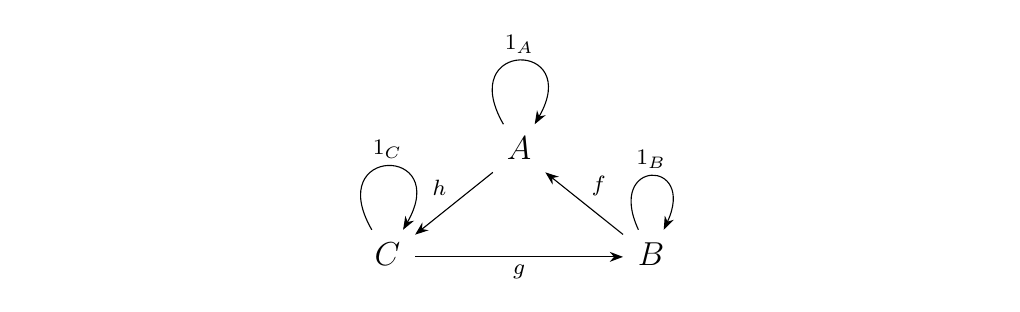

What does the dual category \(\cc\op\) look like? Well, \(\cc\op\)

contains the same objects \(A, B\) and \(C\). As for the morphisms, \(\cc\)

has the three morphisms \(f, g, h\), in addition to their composites.

Therefore, \(\cc\op\) also has three morphisms

\(f\op:B \to A\), \(g\op: C \to

B\) and \(h\op: A \to C\) and their composites. Hence, \(\cc\op\) looks like this:

Let \(P\) be a preorder, specifically a partial order. Recall that this means that \(P\) has a binary relation \(\le\) and if \(p \le p'\) and \(p' \le p\), then \(p = p'\).

We claim that that \(P\op\) is still a partial order. But first, what does \(P\op\) even look like? If we have some elements \(p_1, p_2, p_3\) in \(P\) such that

Then, as a category, \(P\) has the unique morphisms \(f: p_1 \to p_2\) and \(g: p_2 \to p_3\). Hence, in \(P\op\), we have the unique morphisms \(g\op : p_3 \to p_2\) and \(f\op:p_2 \to p_1\), so that we obtain a reversed binary relation \(\le\op\) in \(P\), which reorder \(p_1, p_2, p_3\) as below.

This is kinda weird to write, and in fact, it makes more sense if we write \(\le\op = \ge\) as the binary relation in \(P\op\). We then have that

which is nice! Things are even nicer in a linear order, for if \(P = \{p_1, p_2, p_3, \dots \}\) is a linear order, then we can write that

and hence in \(P\op\) this becomes

Let \((G, \cdot)\) be a group. In group theory one can formulate the opposite group \((G\op, \cdot\op)\) as follows. Define \((G\op, \cdot\op)\) to be group with the same set of elements as \(G\), whose product \(\cdot\op\) works as

Since both \((G, \cdot)\) and \((G, \cdot\op)\) are groups, we can regard them both as one object categories. What is interesting to realize is that under the categorical interpretation, they are opposite categories of each other.

We thus see that dualizing a category simply involves changing the directions of the morphisms on the objects. But can we dualize a functor?

Let \(F: \cc \to \dd\) be a functor and suppose \(f: A \to B\) is morphism in \(\cc\). We say \(F\) is a contravariant functor if \(F(f): F(B) \to F(A)\). This is in sharp contrast to a covariant functor, in which \(f: A \to B\) is sent to \(F(f): F(A) \to F(B)\).

We next introduce a few examples to demonstrate a contravariant functor.

Let \(k\) be an algebraically closed field. Recall that \(A^n(k)\) is the set of tuples \((a_1, a_2, \dots, a_n)\) with \(a_i \in k\). In algebraic geometry, it is of interest to associate each subset \(S \subset A^n(k)\) with the ideal

of \(k[x_1, \dots, x_n]\). Observe that this is always non-empty since \(0 \in I(S)\) for any \(S\). In additional, it is clearly an ideal of \(k[x_1, \dots, x_n]\), since for any \(p \in k[x_1, \dots, x_n]\),\(q \in I(S)\), we have that

so that \(p\cdot q \in I(S)\). Now it's usually an exercise to show that if \(S_1 \subset S_2\) are two subsets of \(A^n(k)\), then one has that \(I(S_2)\subset I(S_1)\). Hence this defines a contravariant functor

where \(**Subsets**(A^n(k))\) is the category of subsets with inclusion morphisms, and \(**Ideals**(k[x_1,\dots, x_n])\) is the category of ideals with inclusion ring homomorphisms.

Consider again \(k\) as an algebraically closed field. In algebraic geometry, one often wishes to associated each ideal of \(k[x_1, \dots, x_n]\) with its "zero set"

It is usually an exercise to show that if \(I_1 \subset I_2\) are two ideals, then \(Z(I_2) \subset Z(I_1)\). Hence we see that this defines a contravariant functor

It is usually at the beginning of an algebraic geometry course that one will understand the relationship between these two constructions, which themselves are secretly functors.

What follows is a very interesting example. In fact, this example is an example of a beautiful concept of a sheaf, and it is usually used as a motivating example. But that is for later.

Let \(X\) be a topological space, and consider the thin category \(**Open**(X)\), which contains all open sets \(U \subset X\), equipped with the inclusion function \(i_{U, X}: U \to X\).

For each \(U \in **Open**(X)\), define the set

Note that if \(U \subset V\) are in \(**Open**(X)\), then we define the function \(\rho_{U,V}: C(V) \to C(U)\) where

That is, \(\rho_{U,V}\) sends continuous, real-valued functions on \(V\) to such functions on \(U\) by restriction. It is not difficult to show that this respects identity and composition requirements, so that we have a contravariant functor

for each topological space \(X\).

What follows is another very important example.

Let \(\cc\) be a locally small category. In this case, we know that each \(A \in \cc\) induces the covariant functor

which sends objects \(C\) to the set \(\hom_{\cc}(A, C)\). It is natural to ask if we may similarly define a functor

The answer is yes. We did not make this observation in the past for pedagogical reasons, since it's actually a contravariant functor (and we didn't know what that was until now). We can now safely say that \(\hom_{\cc}(-, A)\) is a contravariant functor.

We now comment on the relationship between contravariant and covariant functors.

Let \(\cc\), \(\dd\) be categories.

- Let \(F: \cc \to \dd\) be a contravariant functor. Then \(F\) corresponds to a contravariant functor \(\overline{F}: \cc\op \to \dd\) where for a \(f\op : B \to A \in \cc\op\),

$$ \overline{F}(f\op : B \to A) = F(f: A \to B) = F(f): F(B) \to F(A). $$ * Conversely, let \(F: \cc \to \dd\) be a covariant functor. Then \(F\) corresponds to a contravariant functor \(\overline{F}: \cc\op \to \dd\) where

The above proposition allows us to treat any functor as covariant or contravariant. Thus, if we don't like the behavior of our functor on morphisms, we can find an equivalent functor that behaves on morphisms in our preferred way.

Generally, covariant functors are easier to think about, so we often like to turn contravariant functors into covariant functors.

Recall that the functor

is contravariant. What if we want to treat this as a covariant functor? Well, we can define the functor

as follows. If \(U \subset V\) are open subsets of the topological space \(X\), then let \(i: U \to V\) be the inclusion. This is a morphism in \(**Open**(X)\). Hence, \(i\op: V \to U\) is a morphism in \(**Open**(X)\op\). Therefore, we define

Thus we see that this functor \(\overline{C}\) acts the same way as \(C\), except it behaves covariantly on the morphisms now instead of contravariantly.