7.3. What are those Coherence Conditions?

We are now going to address the elephant in the room: we have not explained why we have included diagrams \ref{triangle_diag_1} and \ref{pentagonal_diag} in our definition. To explain this, we are going to discuss the general structure of a monoidal category and answer the natural questions that arise.

Let \((\mathcal{M}, \otimes, I, \alpha, \rho, \lambda)\) be a monoidal category. For objects \(A,B,C, \dots\) of \(\mathcal{M}\), we can use the monoidal product \(\otimes\) to generate various new expressions such as \(A\otimes B\) which represent different objects in \(\mm\). Observe that using three objects, there are two different ways to combine the 3 objects:

There are five ways to combine 4 objects:

And there are 14 ways to combine 5 objects. We will not list them here.

Initially, we don't really know what the relationship is between the various expressions we are generating. For example, we may naturally wonder if

or

have any relation with each other. This is because in practice when \(A,B,C,D\) are sets, vector spaces, groups, or whatnot, the above expressions do have something to do with each other. As we have seen, that relationship is usually an isomorphism. Therefore, if we are to develop some kind of theory of monoidal categories which we can apply to real mathematics, we ought to make sure that these objects are isomorphic in some way.

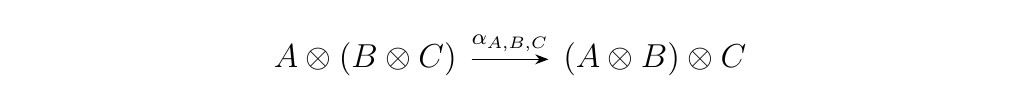

Monoidal categories by definition do in fact provide isomorphisms between different choices of multiplying together a set of objects. For example, from the axioms of a monoidal category, we know that the objects \(A\otimes(B\otimes C)\) and \((A \otimes B) \otimes C\) are related via the natural isomorphism \(\alpha_{A,B,C}\).

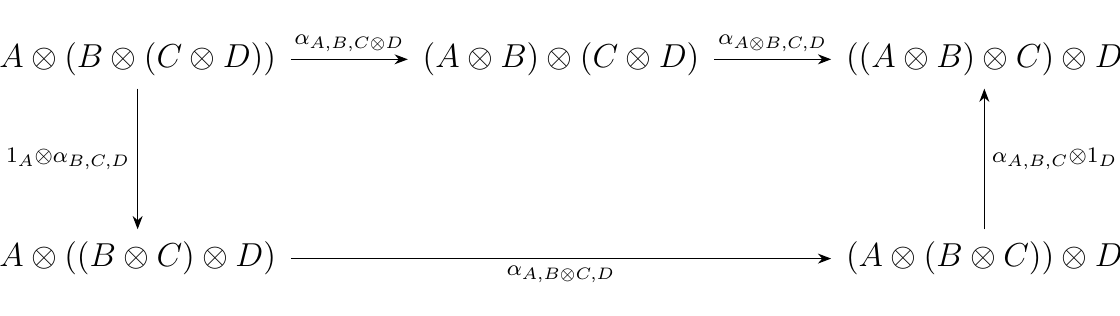

We also know from the axioms of a monoidal category that the 5 products of 4 objects are related via the diagram consisting of natural isomorphisms as below.

Moreover, this diagram is guaranteed to be commutative for all \(A\),\(B\),\(C\),\(D\) in \(\mm\) (we

will elaborate why this is a profound, useful fact).

Moreover, this diagram is guaranteed to be commutative for all \(A\),\(B\),\(C\),\(D\) in \(\mm\) (we

will elaborate why this is a profound, useful fact).

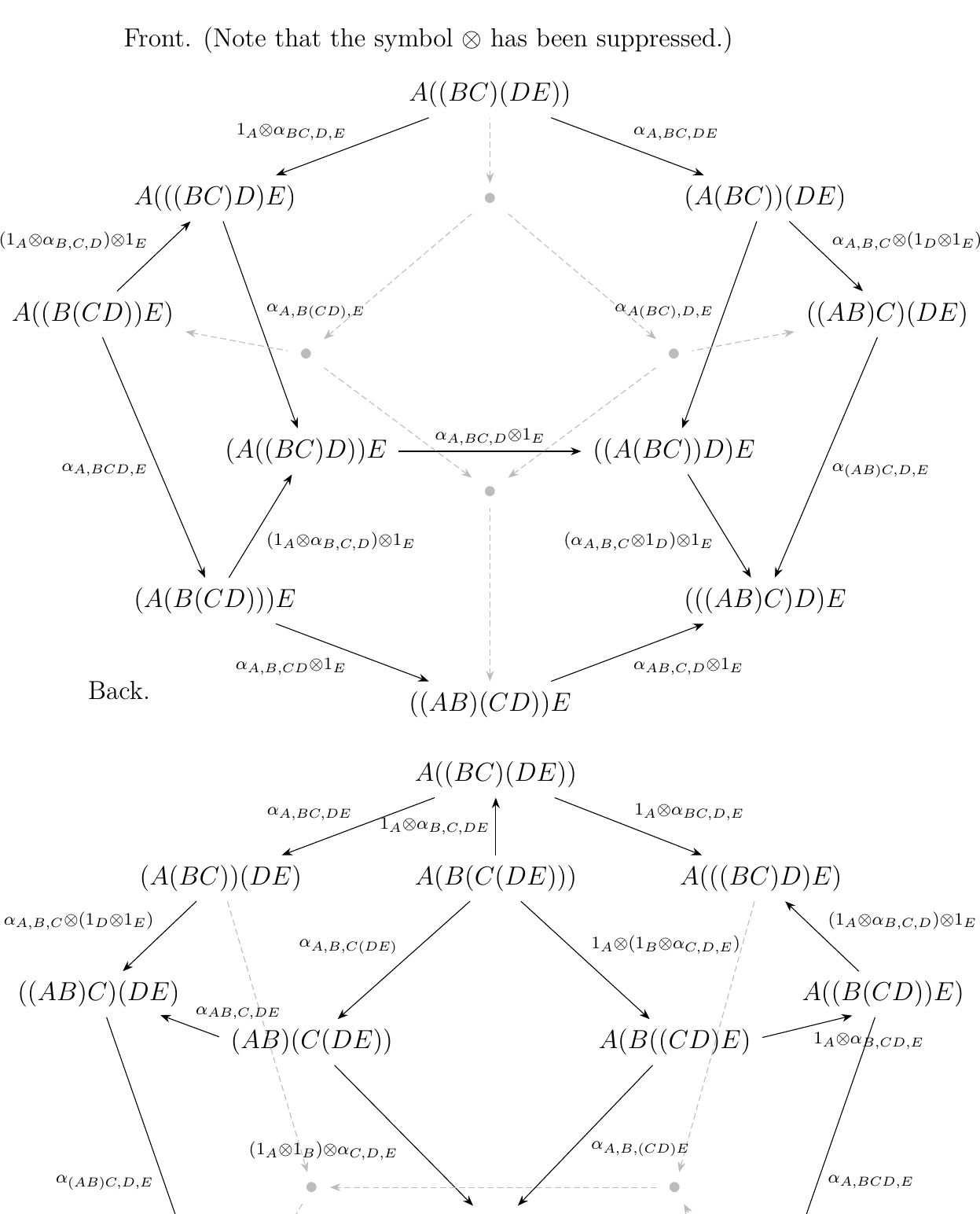

Finally, repeatedly using instances of \(\alpha\), the 14 ways to multiply 5 objects are related via the 3 dimensional diagram as below.

However, it is not an axiom of monoidal categories that this last diagram is commutative

(with a ton of work, one could prove it to be commutative).

However, it is not an axiom of monoidal categories that this last diagram is commutative

(with a ton of work, one could prove it to be commutative).

To understand what's going on, let us first understand why commutativity is important. The axioms of a monoidal category grant us the commutativity of the pentagon, which connects the five different ways of multiplying four objects \(A,B,C,D\). This tells us the following principle: while there are 5 different ways we can multiply four objects \(A,B,C,D\), each such choice is canonically isomorphic to any other choice.

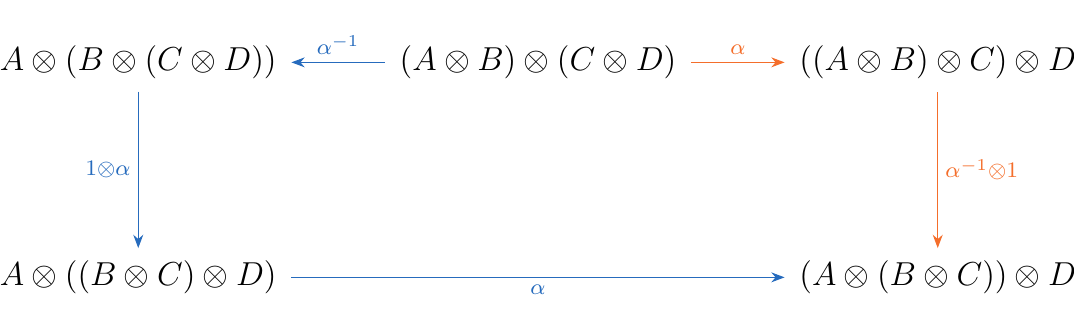

To see this, suppose you and I want to multiply objects \(A,B,C,D\) together. Suppose my favorite way to do it is \((A\otimes B)\otimes(C \otimes D)\), while you choose \((A\otimes(B\otimes C))\otimes D\). Then we might be in trouble: I have two possible ways, displayed below in \textcolor{NavyBlue}{blue} and \textcolor{Orange}{orange}, to "reparenthesize" my product to get your object.

Fortunately, the commutativity of the pentagonal diagram enures that

the two paths are equal. That is,

Fortunately, the commutativity of the pentagonal diagram enures that

the two paths are equal. That is,

so that, in reality, I actually have one unique isomorphism (i.e., a canonical isomorphism) from my object to yours, and you can also canonically get from your object to mine by inverting the unique isomorphism.

However, our choice of two different parenthesizations was arbitrary. The commutativity of the entire diagram therefore tells us that any choice of "parenthesizing" \(A \otimes B \otimes C \otimes D\), the product of 4 objects in \(\mm\), is canonically isomorphic to any other possible choice. This brings up a few questions.

- What do we mean by "parenthesizing?"

- What about a product with \(n\)-many objects \(A\) for \(n > 4\)?

We will rigorously specify what we mean by parenthesizing in a bit. To answer the second question, we state that this result holds for \(n > 4\); this is one version of the Coherence Theorem.