8.4. Kernels and Cokernels

At this point we've discussed preadditive, additive, and preabelian categories, where preabelian categories are just additive categories with the additional hypothesis that kernels and cokernels exist. This additional hypothesis is extremely useful, so we will demonstrate what this implies for us.

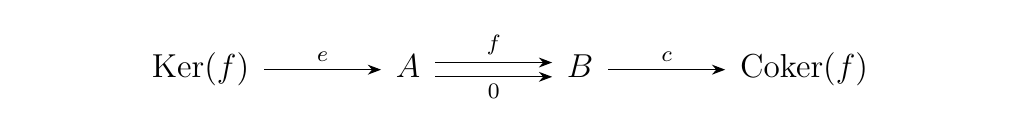

Let \(\cc\) be a preabelian category. Consider an arbitrary morphism \(f: A \to B\). One way to think about kernels and Cokernels is that they give rise to objects in the comma categories \((\cc \downarrow A)\) and \((B \downarrow \cc)\).

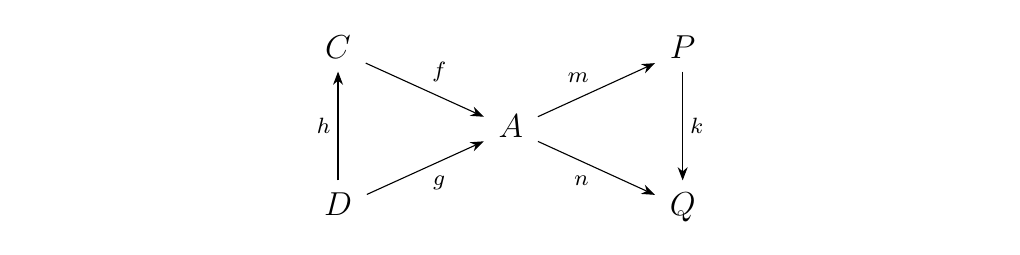

Now in the comma category \((\cc \downarrow A)\), a morphism between two objects

\((C, f: C \to A)\) and \((D, g: D \to A)\) is a morphism \(h: D \to C\) in \(\cc\) such that

\(f = g \circ h\). Similarly, a morphism in the comma category \((A \downarrow \cc)\)

between two objects \((P, m: A \to P)\) and \((Q, n: A \to Q)\) is a morphism \(k: P \to Q\) such that

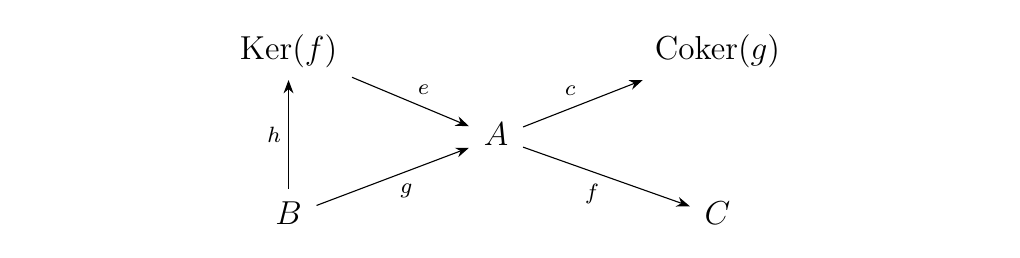

\(n = h \circ m\). These relations give rise to the bow-tie diagram:

Now in the comma category \((\cc \downarrow A)\), a morphism between two objects

\((C, f: C \to A)\) and \((D, g: D \to A)\) is a morphism \(h: D \to C\) in \(\cc\) such that

\(f = g \circ h\). Similarly, a morphism in the comma category \((A \downarrow \cc)\)

between two objects \((P, m: A \to P)\) and \((Q, n: A \to Q)\) is a morphism \(k: P \to Q\) such that

\(n = h \circ m\). These relations give rise to the bow-tie diagram:

With that said, we can actually turn these categories into partial orders.

In \((\cc \downarrow A)\), we say \(g \le f\) if there exists an \(h\) such that \(f \circ h = g\),

and in \((A \downarrow \cc)\), we say \(m \le n\) if there exists a \(k\) such that

\(n = k \circ m\).

With that said, we can actually turn these categories into partial orders.

In \((\cc \downarrow A)\), we say \(g \le f\) if there exists an \(h\) such that \(f \circ h = g\),

and in \((A \downarrow \cc)\), we say \(m \le n\) if there exists a \(k\) such that

\(n = k \circ m\).

It turns out that this perspective is actually quite useful.

Let \(\cc\) be a category with a zero object, equalizers and coequalizers. Then for each object \(A\) of \(\cc\), we have the functors

that assign kernels and cokernels. Moreover, these functors establish a antitone Galois correspondence; hence we have that

Therefore, any \(\phi\) is a kernel if and only if \(\phi = \ker(\coker(\phi))\), while any \(\psi\) is a cokernels if and only if \(\psi = \coker(\psi(\psi))\).

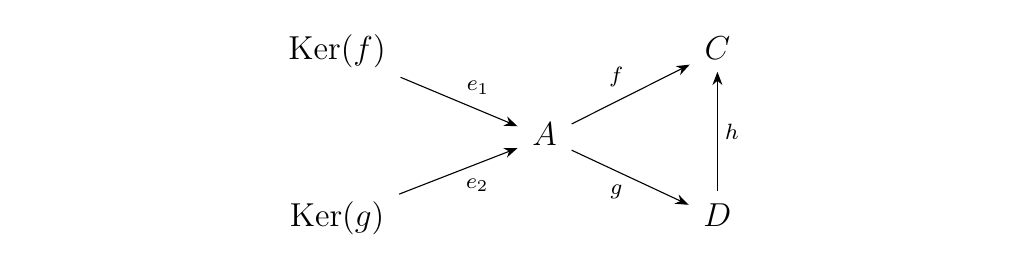

We demonstrate functoriality. First we want our functor to act on objects as

Now we explain how the functor works on morphisms. Suppose we have two objects of our comma category \((C, f: A \to C)\) and \((D, g: A \to D)\), and that \(h: D \to C\) is a morphism in \((A \downarrow \cc)\) from \((D, g: A \to D)\) to \((C, f: A \to C)\). Then we have the diagram below.

Now note that

Now note that

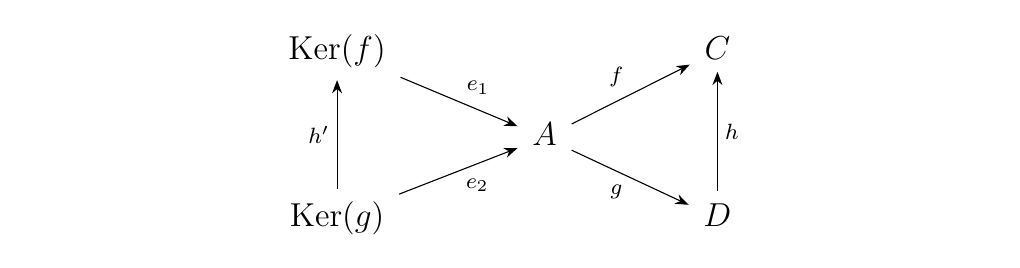

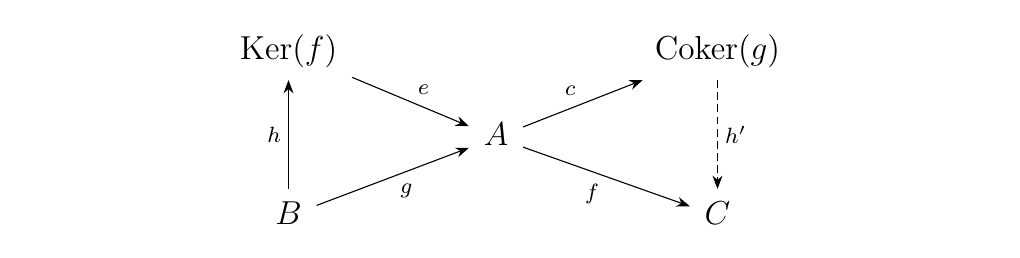

Thus, by the universal property of \(e_1: \ker(f) \to A\), we know there exists a unique morphism \(h': \ker(g) \to \ker(f)\) such that the diagram below commutes.

However, this is exactly what it means to have a morphism between the objects \((\ker(g), e_2: \ker(g) \to A)\) and \((\ker(f), e_1: \ker(f) \to A)\). Thus we see that our functor maps on morphisms in \((A \downarrow \cc)\) in a nice way:

where \(h'\) is the unique map obtained from \(h\) as explained above. With the remaining properties easily verified, this defines a functor between the categories. In addition, we can dualize our work above to also get the functor \(\coker: (\cc \downarrow A) \to (A \downarrow \cc)\).

Now this creates a Galois correspondence by regarding the comma categories as partially ordered sets. Suppose that \(g \le \ker(f)\). That is, there exists a \(h\) such that \(\ker(f) \circ h = g\). Then we can compare \(\coker(g)\) and \(f\) by considering the diagram below.

Now observe that

Now observe that

Therefore, by the universal property of the cokernel, we know there exists a unique morphism \(h': \coker(g) \to f\) such that the diagram below commutes. This then implies that \(f \le \coker(g)\).

By a similar argument, we have that if \(f \le \coker(g)\),

then \(g \le \ker(f)\). Hence we have that

By a similar argument, we have that if \(f \le \coker(g)\),

then \(g \le \ker(f)\). Hence we have that

so that, as preorder, the kernel and cokernels functors are adjoint pairs that form an antitone Galois correspondence. Moreover, this implies that for each \(f: B \to A\) and \(g: A \to C\),

In particular, if \(f\) is the cokernel of some morphism \(\phi\), and if \(g\) is the kernel of some morphism \(\psi\), then we have that

However, applying the order reversing functors \(\coker\) and \(\ker\) on the relations \(\phi \le \ker(\coker(\phi))\) and \(\psi \le \coker(\ker(\psi))\) yields

Hence we have that \(\coker(\ker(\coker(\phi))) \cong \coker(\phi)\) and \(\ker(\coker(\ker(\psi))) \cong \ker(\psi)\) as desired.